16 Mar 2016 Mechanisms of Control: How Turkey is Criminalizing Dissent and Muzzling the Press in National Security and Defense

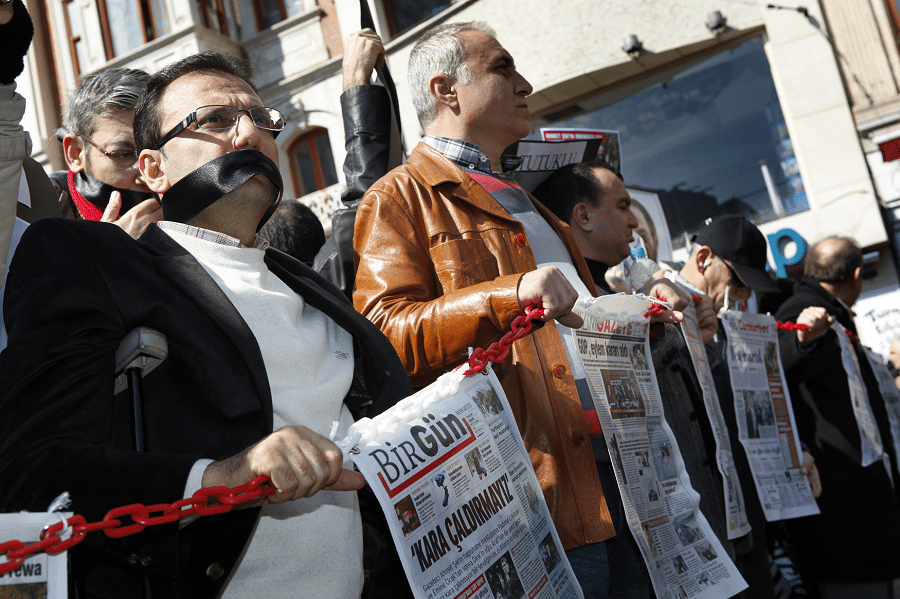

Through its mounting campaign of arrests, financial pressure, online censorship, outright seizure, and violent intimidation, Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has been increasingly successful in muzzling Turkey’s outspoken press. This assault on media freedom has been most visible over the course of the last two years, during which Turkey held four elections. But the AKP’s attempts to control the press cannot simply be chalked up to heavy-handed electoral tactics. The Bipartisan Policy Center’s analysis of the mechanisms—both legal and extralegal—that the AKP regime has used to control the media shows an interest in controlling the press going back to at least 2008. Furthermore, it shows how the government has perfected new, increasingly aggressive means to pressure the press, with a chilling effect on the willingness of both Turkish media and society to dissent from the official government line.

Turkish government attacks on the media are part of a larger strategy of dismantling any institutions—the military, the judiciary, and now the media—capable of acting as a check on the AKP’s power. With its increasingly tight grip on the formerly independent institutions of the state and the media, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the AKP are creating an autocratic society— but they are not buying stability. Biased reporting—and, in some cases, deliberate misinformation—are used to build support for Turkey’s destabilizing civil war with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey’s southeast, as well as a Syria policy increasingly at odds with U.S. interests. Indeed, in recent years U.S.-Turkish disagreement over confronting ISIS reached the point where an exasperated Vice President Joe Biden declared, “Our biggest problem is our allies.”

American policymakers concerned about the direction of Turkish foreign policy must pay greater attention to the health of Turkey’s democracy and, in particular, the state of its media. A change in Turkish policy cannot come absent the expression of dissatisfaction at the country’s current direction from a majority of voters. But how are they to know what is happening inside Turkey, let alone on its periphery, if the government is preventing the media from reporting on sensitive subjects and silencing any voice that is critical of its policies? Also troubling is recent evidence that Turkey’s approach to managing its own media—by peddling disinformation through cowed and compliant channels—has spilled over into its diplomatic relations with the United States, corroding much needed trust between the two countries.

“If you do not have the ability to express your own opinion, to criticize policy, offer competing ideas without fear of intimidation or retribution,” as Biden put it on a January 2016 visit to Turkey, “then your country is being robbed of opportunity.” And if the United States does not express its opinions about the suppression of media freedom in Turkey, it is robbing itself of the opportunity to repair what once was, and should again be, a close alliance and productive partnership.

The State of Turkey’s Media

While the AKP’s early years in power were marked by slowly improving press freedom, as shown by Freedom House’s yearly Freedom of the Press rankings, press freedom began to drop precipitously after 2008, until Turkey’s press was demoted from “partly free” to “not free” in 2014.

When the AKP began its tenure in 2002, it released journalists imprisoned by Turkey’s previous rulers, consistent with the image the AKP promoted of itself as liberal, democratic reformers intent on European Union membership and integration with the West. However, the legal framework used by Turkey’s past leaders to imprison journalists was not dismantled, only temporarily unused. Intent on transforming Turkish society as part of what he calls the “New Turkey” project, Erdoğan and the AKP began to abandon their image as reformers, and to use these repressive laws to prosecute their opponents, instead of reforming or repealing them. The numbers are startling: in 2012 and 2013, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) ranked Turkey as the world’s worst jailer of journalists.